|

At the February 2026 Logan County

Genealogical and Historical Society meeting, Anna Sielaff hosted a

presentation titled “Relive the True Mother Road: the Edwards Trace

and how Illinois developed before it became a state.”

Sielaff, who was born and raised in

Lincoln, is the local history librarian at the public library in

Springfield. She works in the Sangamon Valley collection, which is

their local archive. This collection covers Sangamon County and

surrounding counties such as Logan County. Sielaff recently became a

Rhodes scholar and during the 250th anniversary of the United States

this year will travel throughout the state doing programs. Besides

Edwards Trace, she also does a program on women’s baseball.

Since she was 13 years old, Sielaff has been researching Edwards

Trace. Her goal for the program was to give everyone a broad

perspective of how Illinois developed before and after it became a

state in 1818.

Illinois has a rich history not

many people know about. For instance, Sielaff said when we think

about the colonial era, some of us think about the East Coast. We

have to remember though there were actually Europeans here in the

area before the 1700s.

The Edwards Trace is ancient trail

that is over 3000 years old and runs through Illinois marking the

seasonal migratory path of herds and animals. It was used by the

Native Americans to follow the migrations and hunting, trade and

war. The Trace was the main route from Kaskaskia in Southern

Illinois to present day Peoria. Both Kaskaskia and Peoria were

French settlements. Sielaff called Edwards Trace the “Route 66” of

its time.

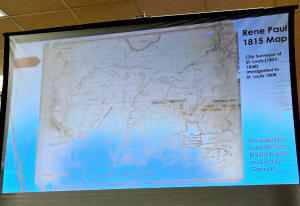

As an archivist, Sielaff loves

looking at old maps. An 1815 map of the Illinois Territory made by

St. Louis city surveyor Rene Paul shows the Edwards Trace starting

near Edwardsville and going up to Lake Peoria.

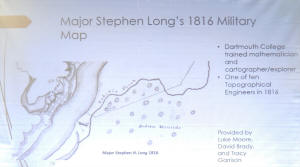

An 1816 military map by Dartmouth

College’s trained mathematician and cartographer/ explorer major

Stephen Lang also shows parts of Edward’s Trace. Lang was charged

with looking at the fortifications in the Illinois territory and

seeing how improvements could be made. On his travels, he passed

Edwards Trace and the Cahokia Mounds.

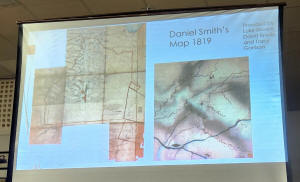

In addition, Daniel Smith’s 1819

map has dotted lines with towns like Elkhart labeled. Smith was

involved in the Kickapoo Treaty deliberations in Edwardsville when

he drafted this map to show landmarks the Kickapoo would recognize.

Sielaff said the dotted lines show Edward’s Trace near Elkhart.

These maps are great primary documents showing the existence of the

Edwards Trace.

There were many native tribes in

the area in the 17th and 18th centuries. The 17th century native

tribes in Illinois were the Illinois also known as the Illiniwek

confederation and a group of tribes that included the Peoria,

Kaskaskia, Tamaroa and Michigamea. Sielaff said they shared similar

languages and customs. The 18th century native tribes in Illinois

included the Sauk, Fox, Kickapoo, Miami and Powatami tribes.

Sielaff said Native Americans used the trail because it provided an

easier way to travel during the harsh winter conditions when the

lakes were frozen. The trail was still accessible. The path from

Edwardsville to Peoria was about 146 miles long.

To explain the difference between a trace and a trail, Sielaff said

a trace is a mark left by someone or something so it could be a path

trail footprint or sign of something that existed years ago. A trail

is used specifically to refer to a path that someone took.

In the 17th century, French

explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet travelled the

Mississippi River hoping to find a waterway that emptied into the

Pacific Ocean. Sielaff said they followed the Mississippi to

Arkansas and that opened the area to other French explorers and fur

traders.

[to top of second column] |

The French were

the first Europeans in Illinois to contact Native Americans, and

the first to govern the land and build forts. The French

established missionaries in Cahokia in 1699 and Kaskaskia in

1703, which Sielaff said makes them the oldest towns in Illinois

These French explorers established outposts by the Mississippi

River while seeking a route to the ocean and looking for gold

and other riches as they travelled south. Sielaff said they

instead found good soil, which is now know the American bottom,

a fluvial plain between the Mississippi River and the cliffs

where Kaskaskia is located.

Fort De Charles in Prairie De Rocher is the first French

settlement built in southern Illinois. Sielaff said it was the

French headquarters but never saw battles. It was built as a

symbol to show French power.

French Cahokia, the Cahokia courthouse and the 1799 Church of

the Holy Family are places still standing in Cahokia, Illinois.

All the priests who preached there are buried behind the church.

Archeologist and historian Robert Mazrim did extensive research

on the Edwards Trace. Mazrim talked about recognizing the

importance of trails, especially ones linking French villages to

the American bottoms.

French and Indian War links to Edwards Trace

In 1778 George Rogers secured Kaskaskia for the United States.

During the Revolutionary War, Sielaff said Kaskaskia was still

populated by French settlers and Clark’s victory doomed British

control there when he captured the British headquarters. He

travelled a portion of the Edwards Trace when he travelled from

Kaskaskia to Cahokia. British officer Henry Hamilton called for

a counterattack at Kaskaskia. His travels led him from Fort

Detroit in Michigan to Vincennes, Indiana.

The western liberty bell, given by King Louis IV to the Catholic

Church in in the Illinois County was rung in Kaskaskia to

celebrate after Clark captured the town July 4th, 1778. Sielaff

said this bell is still rung every July 4th

Kaskaskia was the first state capital. In 1993, Kaskaskia was

ravaged by flood.

French called the area Kaskaskia

Cahokia trail in the 1700s and this trail is still travelled 300

years later. Ninian Edwards, who was a legislator judge and then

territorial governor of Illinois in early 1800s, is where Edwards

Trace got its name. It was Edwards who oversaw Illinois’ transition

into statehood. Sielaff said Edwards was married to Mary Todd

Lincoln’s sister, so there was a connection to Abraham Lincoln

The War of 1812 involved disputes over shipping rights on the open

seas. It was known as an Indian war as it pitted Native Americans

loyal to British against the Americans settlers.

Sielaff said in an attack at Fort Dearborn near Chicago, 66 American

settlers and 15 Potawatomi died. Potawatomi tribe member Black

Partridge supported the white settlers and saved many settlers

during the attack. Tensions between the Kickapoo and the Potawatomi

were high.

A massacre at Fort Dearborn prompted Edwards to form a militia of

rangers to take the trail to attack the Potawatomi Indians. Sielaff

said when Black Partridge saw damage to his village, he and his

tribe attacked Fort Russell.

After this campaign, the trail was named in honor of Edwards and

became the main route of travel from the north to the south. Even

now it goes near Springfield and Lincoln.

Nearby connections to Edwards Trace

Sielaff said James Latham, who was the first white Logan County

settler, purposefully put his family farm near the Edwards Trace on

Elkhart hill.

An 1819 map shows Kickapoo village in Lincoln. In 1790, in what is

now Memorial Park in Lincoln, the Gilham family wife and children

were abducted by the Kickapoo and taken all the way to Kickapoo

town. Anne Gilham is reported to have been the first Caucasian woman

to lay eyes on Logan County. Sielaff said an 1815 map shows Kickapoo

town along Edwards Trace. Trail trees were flexible saplings that

give directions as people traveled and one can be found in Memorial

Park in Lincoln.

Other Illinois areas on or near Edwards Trace include Robert

Musick’s home, a trail near Hartsburg, Buffalo Hart and Lake

Springfield. At Lake Springfield, Sielaff said there is this

historical marker noting Edwards Trace.

Zimri Enos said a trail or trace as an interesting matter of history

should be established before all evidence of its location is gone.

Unfortunately, the trace is in danger of being destroyed.

Over 20 years Luke Moore, David Brady and Tracy Garrison have been

studying Edward's Trace and using LIDAR to find sections of it.

Sielaff has created an interactive story and website to share some

of the information she has found. To learn more, contact her at

annasielaff98@gmail.com

LCGHS Edwards Trace Presentation photo slideshow

[Angela Reiners] |